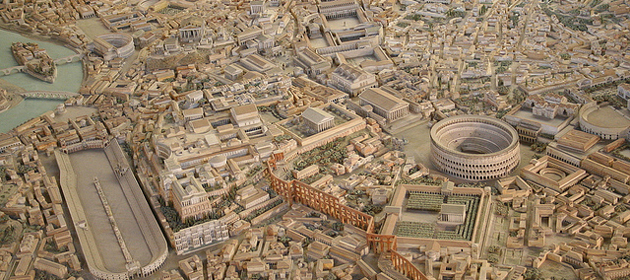

The very existence of Rome’s urban landscape is a history lesson. It is a unique experience to walk its streets. Layers of the past pile on top of each other into an amalgam over two thousand years in the making. Renaissance constructions, built in the midst of medieval structures, have in turn have been repurposed from ancient ruins. Vestiges of a time gone by, still visible and tangible, stand as silent monuments to the appropriately named “eternal city.”

Even in the context of ancient Rome by itself, the city’s urban landscape changed drastically over time. What began as a conglomeration of tribes atop seven hills developed into one of the world’s most impressive and renowned metropolises. As a game designer, how do you even begin to reflect the enormity that is Rome? How do you teach accurately, yet maintain a spacial structure that supports fun gameplay? How do you make real the concrete through the abstract? These questions may seem (and often are) daunting, but game designers have been tackling tasks just like this for decades.

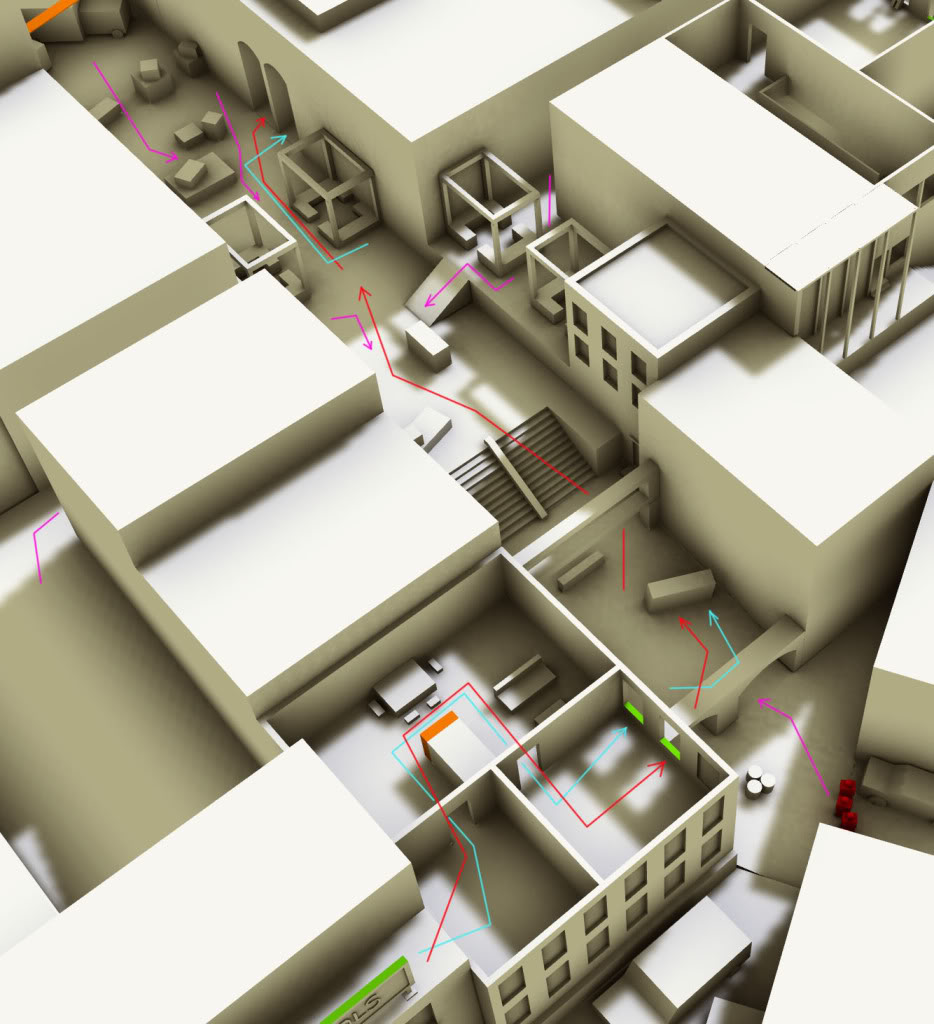

In this week’s post I will be examining a process referred to as “greyboxing,” a common technique used in level design. But before we dive into this process, let’s first examine the important difference between what can be referred to as “Real” space and “Game” space. “Real” space is what is all around us, the literal distance between objects and the exact dimensions of physical objects. “Real” space is often what we try to emulate through the design of “Game” space.

“Game” spaces are often much simpler than “Real” spaces. They really need to be, for several reasons! First, “Game” spaces must serve a functional purpose, that is they must support the mechanics of the game. Ideally, if you were to strip all of the art away from a scene, the functionality of the game would remain unchanged. This is not to say that art is not an essential part of the end experience, far from it, but when building game environments from the ground up, it is important to remember that a designer is building a game first, and that this fundamental reality supports every aspect of what the team is trying to convey. Even studios like Naughty Dog that are revered for their artistic polish, known for games like the Uncharted series, still use this fundamental design technique when building their levels.

Second, “Real” spaces are often too large or complex to be enjoyed from the systemic nature games ask players to accept. It takes hours to walk from one side of Rome to the other in real life; this alone would make a dull, uninteresting, and frustrating game. In the first iteration of Saeculum, this was one of the major issues we encountered. The levels were just too big! It took players too long to get anywhere and it was difficult to make spaces feel interesting.

Third, it is a technical necessity. Developers must be smart when designing a game. Games enable immersion through realtime interactivity, and computers do not have infinite processing power. The clever design of “Game” space can go a long way to preserving the feel of a “Real” space without the need to replicate it down to a laser-exact degree.

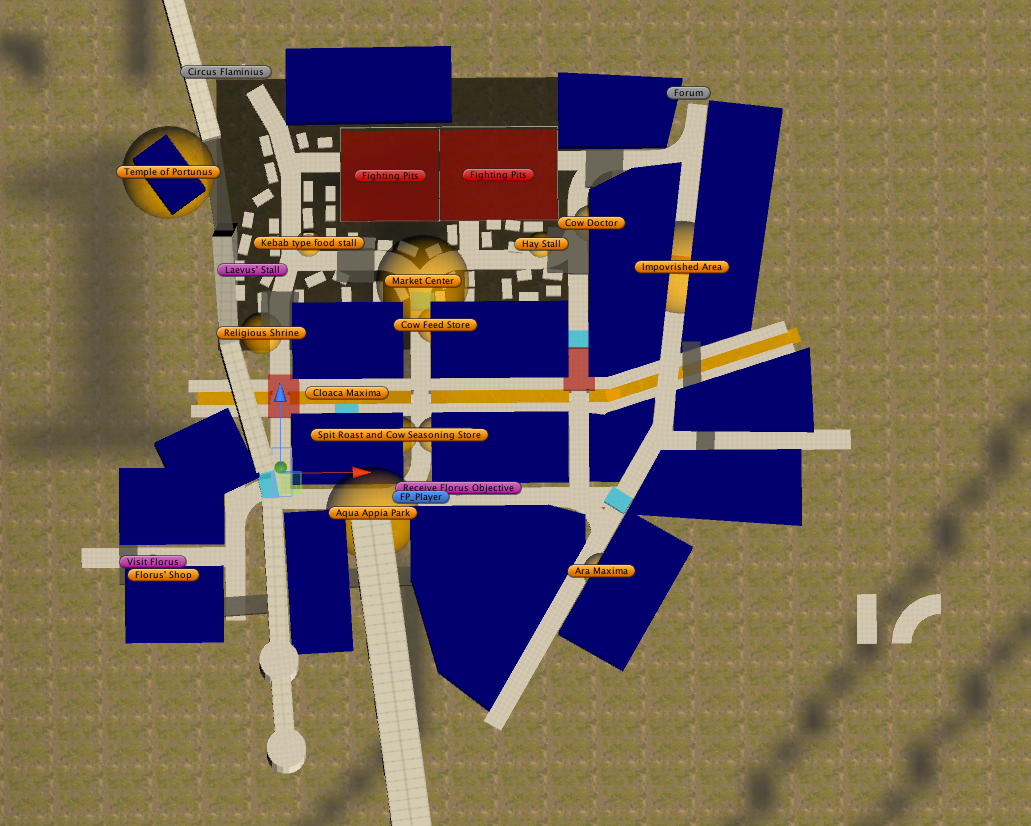

Let’s take a look at an example from one of the newly designed levels in Saeculum: the Forum Boarium in Arc 1, which takes place between the years 220-202 BCE.

When sitting down to design a level for Saeculum, a designer must take into account several factors.

- First, and most obviously, is the historical setting for the level being designed. There are several landmarks the designer had to incorporate based on the area’s historical evidence including temples, a sewer drain called the Cloaca Maxima, and the Servian Wall, which surrounded the early city.

- Second, the designer must arrange locations where players complete objectives, as directed by the script. It is one thing to put words on a page, but it is another entirely to realize this narrative within the context of “Game” space.

- Third, the designer must create spaces designated for encounters, areas where players will happen upon combat, engage in debates, or have to sneak through unseen. All the while the designer must keep in mind a balance of spacing and meaningful player choice when it comes to choosing how a player navigates Rome’s streets.

- On top of all this, designers must develop the underlying narrative of the level (what we internally refer to as “level lore”) in conjunction with the main story in the script and the historical evidence of both the time period and specific location within Rome.

As you can see, this is not a simple process! It takes a lot of hard work and honed technique to tune the levels so that they can be a reliable teaching tool, despite the fact that they are technically an abstraction of reality.

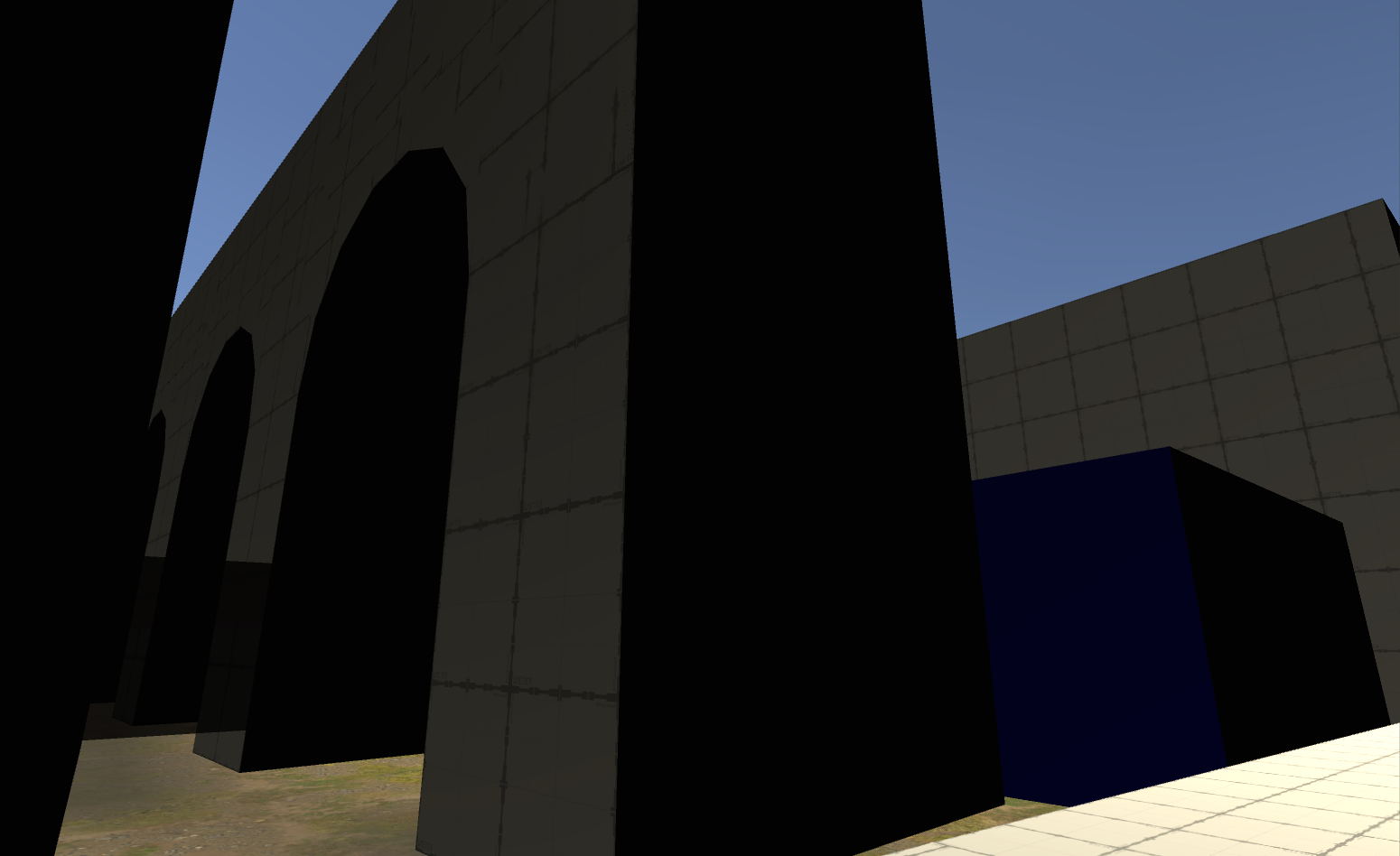

After a greybox has been established, however, the work is not over. The Design team must collaborate with Environmental Artists to transform the functional outline into a true work of art.

It’s amazing to see the process in action, even after only a single art pass.

Without a firm blueprint from which gameplay can be developed, “Game” space can become aimless, without purpose, and difficult to associate with the game’s core mechanics. But using “greyboxing” as a key technique gives structure and opens gateways so the development team can fully realize their artistic vision.