Post by Game Design I student Diego Calderon

Jesse Schell explains in his book, “The Art of Game Design”, that there are four essential elements in a game: Mechanics, Story, Aesthetics, and Technology. He refers to these elements as an Elemental Tetrad.

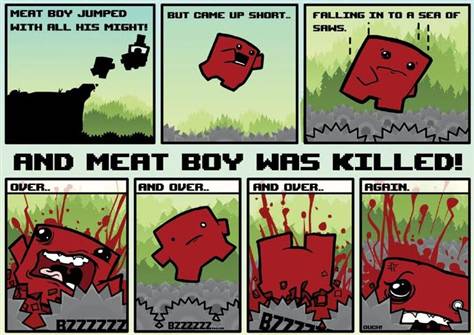

Aesthetics are the most visible element of a game. Super Meat Boy may look weird to someone who is not playing it. It is hard to understand: a skinless boy getting killed over and over again by saws, needles, or salt.

Jesse Schell explains in his book, “The Art of Game Design”, that there are four essential elements in a game: Mechanics, Story, Aesthetics, and Technology. He refers to these elements as an Elemental Tetrad.

Aesthetics are the most visible element of a game. Super Meat Boy may look weird to someone who is not playing it. It is hard to understand: a skinless boy getting killed over and over again by saws, needles, or salt.

Super Meat boy has a linear story. You are a boy that is trying to save a girl. There is nothing “super” about Meat Boy, other than he will try over and over until he gets to her. Sadly, when he gets to his girlfriend, Dr. Fetus kidnaps her again.

Super Meat boy has a linear story. You are a boy that is trying to save a girl. There is nothing “super” about Meat Boy, other than he will try over and over until he gets to her. Sadly, when he gets to his girlfriend, Dr. Fetus kidnaps her again.

Mechanically, as in every platformer, you can walk and run but you can only “single jump”. What makes it different is that you can climb walls by “wall jumping”. You have infinite lives and the penalty for dying is that you re-spawn at the beginning of the level. You encounter no monsters, you only die (instantly) from hazards that you find along your path, such as saws. Did I mention there is a lot of blood?

Super Meat Boy uses Flash for art and animation and it is written in C++. The designers intended the game to be played with a controller, even if you are playing it on a computer. You can see some hints they leave when you start the game:

Mechanically, as in every platformer, you can walk and run but you can only “single jump”. What makes it different is that you can climb walls by “wall jumping”. You have infinite lives and the penalty for dying is that you re-spawn at the beginning of the level. You encounter no monsters, you only die (instantly) from hazards that you find along your path, such as saws. Did I mention there is a lot of blood?

Super Meat Boy uses Flash for art and animation and it is written in C++. The designers intended the game to be played with a controller, even if you are playing it on a computer. You can see some hints they leave when you start the game: All these elements don’t make much sense on their own. If you only see the aesthetic part of the game, it can be scary and not very appealing. However, if you put together the story and those looks, it starts to make more sense. Meat Boy is, what the name may imply, a boy with no skin. His girlfriend, Bandage Girl, is a girl made of bandages. Together Meat Boy and Bandage Girl make sense; they complement each other. The same thing happens with the elements of a game. Without one of them, the game makes no sense. It ceases to exist.

All these elements don’t make much sense on their own. If you only see the aesthetic part of the game, it can be scary and not very appealing. However, if you put together the story and those looks, it starts to make more sense. Meat Boy is, what the name may imply, a boy with no skin. His girlfriend, Bandage Girl, is a girl made of bandages. Together Meat Boy and Bandage Girl make sense; they complement each other. The same thing happens with the elements of a game. Without one of them, the game makes no sense. It ceases to exist.

A game has boundaries. If you try to leave those boundaries something must happen. If you try to do so in Super Meat Boy, you die and re-spawn in the beginning of the level. A game must have a place where it exists, where it makes sense. In “Rules of Play”, the authors (Eric Zimmerman and Katie Salen) define a “magic circle” of a game as the space where it takes place.

A game has boundaries. If you try to leave those boundaries something must happen. If you try to do so in Super Meat Boy, you die and re-spawn in the beginning of the level. A game must have a place where it exists, where it makes sense. In “Rules of Play”, the authors (Eric Zimmerman and Katie Salen) define a “magic circle” of a game as the space where it takes place.

When you combine all these essential elements, like the technology that enables the mechanics, the mechanics that strengthen the story, and the aesthetics that reinforce the ideas of the story, you create a playable game. A place where a player may decide to play and to stop playing. A place where all the rules of the system make sense and give something back to the player. Schell makes it clear that every element in the Elemental Tetrad is equally important, and that they support and strongly influence each other. If you take one out, there is no magic circle. If there is no magic circle, the game can’t be alive.

In “Rules of Play” the authors explain the concept of explicit interactivity as the participation between designed choices and procedures programmed into the interactive experience. When you enter the magic circle, you interact with the set of rules that come alive in those boundaries. In other words, you interact with the combination of the elements of the Elemental Tetrad. This interaction between the player and the magic circle is what delivers an experience.

When you combine all these essential elements, like the technology that enables the mechanics, the mechanics that strengthen the story, and the aesthetics that reinforce the ideas of the story, you create a playable game. A place where a player may decide to play and to stop playing. A place where all the rules of the system make sense and give something back to the player. Schell makes it clear that every element in the Elemental Tetrad is equally important, and that they support and strongly influence each other. If you take one out, there is no magic circle. If there is no magic circle, the game can’t be alive.

In “Rules of Play” the authors explain the concept of explicit interactivity as the participation between designed choices and procedures programmed into the interactive experience. When you enter the magic circle, you interact with the set of rules that come alive in those boundaries. In other words, you interact with the combination of the elements of the Elemental Tetrad. This interaction between the player and the magic circle is what delivers an experience.

Jesse Schell explains in his book, “The Art of Game Design”, that there are four essential elements in a game: Mechanics, Story, Aesthetics, and Technology. He refers to these elements as an Elemental Tetrad.

Aesthetics are the most visible element of a game. Super Meat Boy may look weird to someone who is not playing it. It is hard to understand: a skinless boy getting killed over and over again by saws, needles, or salt.

Jesse Schell explains in his book, “The Art of Game Design”, that there are four essential elements in a game: Mechanics, Story, Aesthetics, and Technology. He refers to these elements as an Elemental Tetrad.

Aesthetics are the most visible element of a game. Super Meat Boy may look weird to someone who is not playing it. It is hard to understand: a skinless boy getting killed over and over again by saws, needles, or salt.

Mechanically, as in every platformer, you can walk and run but you can only “single jump”. What makes it different is that you can climb walls by “wall jumping”. You have infinite lives and the penalty for dying is that you re-spawn at the beginning of the level. You encounter no monsters, you only die (instantly) from hazards that you find along your path, such as saws. Did I mention there is a lot of blood?

Super Meat Boy uses Flash for art and animation and it is written in C++. The designers intended the game to be played with a controller, even if you are playing it on a computer. You can see some hints they leave when you start the game:

Mechanically, as in every platformer, you can walk and run but you can only “single jump”. What makes it different is that you can climb walls by “wall jumping”. You have infinite lives and the penalty for dying is that you re-spawn at the beginning of the level. You encounter no monsters, you only die (instantly) from hazards that you find along your path, such as saws. Did I mention there is a lot of blood?

Super Meat Boy uses Flash for art and animation and it is written in C++. The designers intended the game to be played with a controller, even if you are playing it on a computer. You can see some hints they leave when you start the game: All these elements don’t make much sense on their own. If you only see the aesthetic part of the game, it can be scary and not very appealing. However, if you put together the story and those looks, it starts to make more sense. Meat Boy is, what the name may imply, a boy with no skin. His girlfriend, Bandage Girl, is a girl made of bandages. Together Meat Boy and Bandage Girl make sense; they complement each other. The same thing happens with the elements of a game. Without one of them, the game makes no sense. It ceases to exist.

All these elements don’t make much sense on their own. If you only see the aesthetic part of the game, it can be scary and not very appealing. However, if you put together the story and those looks, it starts to make more sense. Meat Boy is, what the name may imply, a boy with no skin. His girlfriend, Bandage Girl, is a girl made of bandages. Together Meat Boy and Bandage Girl make sense; they complement each other. The same thing happens with the elements of a game. Without one of them, the game makes no sense. It ceases to exist.

A game has boundaries. If you try to leave those boundaries something must happen. If you try to do so in Super Meat Boy, you die and re-spawn in the beginning of the level. A game must have a place where it exists, where it makes sense. In “Rules of Play”, the authors (Eric Zimmerman and Katie Salen) define a “magic circle” of a game as the space where it takes place.

A game has boundaries. If you try to leave those boundaries something must happen. If you try to do so in Super Meat Boy, you die and re-spawn in the beginning of the level. A game must have a place where it exists, where it makes sense. In “Rules of Play”, the authors (Eric Zimmerman and Katie Salen) define a “magic circle” of a game as the space where it takes place.

When you combine all these essential elements, like the technology that enables the mechanics, the mechanics that strengthen the story, and the aesthetics that reinforce the ideas of the story, you create a playable game. A place where a player may decide to play and to stop playing. A place where all the rules of the system make sense and give something back to the player. Schell makes it clear that every element in the Elemental Tetrad is equally important, and that they support and strongly influence each other. If you take one out, there is no magic circle. If there is no magic circle, the game can’t be alive.

In “Rules of Play” the authors explain the concept of explicit interactivity as the participation between designed choices and procedures programmed into the interactive experience. When you enter the magic circle, you interact with the set of rules that come alive in those boundaries. In other words, you interact with the combination of the elements of the Elemental Tetrad. This interaction between the player and the magic circle is what delivers an experience.

When you combine all these essential elements, like the technology that enables the mechanics, the mechanics that strengthen the story, and the aesthetics that reinforce the ideas of the story, you create a playable game. A place where a player may decide to play and to stop playing. A place where all the rules of the system make sense and give something back to the player. Schell makes it clear that every element in the Elemental Tetrad is equally important, and that they support and strongly influence each other. If you take one out, there is no magic circle. If there is no magic circle, the game can’t be alive.

In “Rules of Play” the authors explain the concept of explicit interactivity as the participation between designed choices and procedures programmed into the interactive experience. When you enter the magic circle, you interact with the set of rules that come alive in those boundaries. In other words, you interact with the combination of the elements of the Elemental Tetrad. This interaction between the player and the magic circle is what delivers an experience.