Listen –

I am tasked with breathing acoustic life into Walking in Guy's Brooklyn (WGB) – a video game based around Francis Guy’s painting Winter Scene in Brooklyn (Figure 1, above). In the different parts of the game, the player takes their avatars to a number of locations that would have been frequented by 1810s Brooklynites, including the intersection of Front St. and James St. represented in Guy’s painting.

Now, I was born about two-hundred years too late and a thousand miles too far to the west to truly hear the scene itself – the slish of sleds through slush; the dull, splashy snow-steps of chickens’ feet, cows’ and horses’ hooves, hogs’ trotters, and humans’ boots; the pealing of ships’ bells from just down the street and across the East River; the myriad voices of foreign transplants (willing or otherwise), commercial visitors, and life-long New Yorkers, all laughing and crying and shouting and pontificating and barking orders and capitulating to the same in a world-atlas of tongues and dialects: Dutch, French, German, myriad bricolages of Caribbean and West-African Creole, and – of course – English. We will never personally hear, in situ, the songs of Master Sweeps and their chimney-climbing charges jockeying for sonic space amid the crush of seagull squawks, crow calls, and all the human music of commerce and conversation. Time and space deny us direct access to the soundscape dispassionately drumming Guy's ear as he dabbed his brushes and called out to the people below his window to stand still so he could capture their poses.

A hand puts paint on canvas. There the pigments dry, and the whole ensemble holds a (fabricated and distorted, but nevertheless plausible) picture of a place, keeping this image steady and accessible for so long as the painting is maintained, occasionally recuperated by steady, professional hands in sterile rooms, and displayed before the eyes of the public. It can be photographed by professionals and amateurs alike, and those photographs can be duplicated and disseminated until the visual approximation of a snow-covered street in Brooklyn circa the first Monroe administration is rendered virtually endless and immortal through the Internet, and those physical canvasses purported to have been touched by the man himself (and possibly his wife) gain the aura of the original artifact, worthy of display on venerable, thoughtfully-lit walls in carefully curated, well-funded spaces around the world [Footnote 1]. The ossification and dissemination of the seen world through the visual arts is nothing new – human beings have been preserving and duplicating visual impressions for at least ten-thousand years. We even know roughly what our ancient ancestors thought of the beasts they caught, killed, and captured in finger-paintings on the walls of caves.

But we no more know what those ancient beasts sounded like to our ancestors than we know for certain what kinds of vibrations exactly tickled Guy’s eardrums through the open window on those not-so-distant winter days of yore. There was no way for the painter to produce a physical recording of the soundscape beyond his window – the earliest prototype of audio recording technology was still forty years distant [Footnote 2], the ability to play back recorded sound wouldn’t be achieved for another twenty years after that [Footnote 3], and these recordings wouldn’t start to sound aesthetically passable (which is to say, reasonably high-fidelity) to our spoiled 21st-century sensibilities for another seventy or so years after that [Footnote 4]. The upshot here is there are no faithful, in situ recordings of early 19th soundscapes – no original artifacts which captured the ear-drumming physical vibrations of the time.

Or aren’t there? Certainly there are written remarks on the acoustic landscape from contemporary sources. Human beings have recorded their observations of urban sounds for far longer than they have recorded the sounds themselves [Footnote 5]. Thus, we do have some 19th century remarks on the audible aspects of life in New York City and environs: a little book of cries and calls [Footnote 6], and a history of Brooklyn that includes reference to particular notable noises [Footnote 7]. Besides written evidence, I can also use the painting itself (and interpretive literature about the painting) as a guide to deducing which sounds probably would have fallen on Guy’s ears – such deduction informed Paragraph 3 above.

But this written imagery – no matter how colorful it may be – is not enough for the emotive demands of video game audio. It is not enough to simply tell a player what their avatar can hear. Engaging experience and fascinating play depend on immediate sensation; the sound designer must put the player there in the scene. Like in 3D, first-person perspective games, where the player is privy to the immediate virtual-physical surroundings and stimuli acting on the avatar [Footnote 8], in 2D, menu-intensive games, sound design provides sensational depth to the visual components of the game. However, because 2D games don't provide the same immediacy of "embodied" spatial experience, the importance of aural components as equal partners to visual components in the cultivation of immersion comes to the fore.

To demonstrate what I mean, I want you to do a quick exercise:

- Step away from your screen, and go somewhere you can remain unmolested for a few minutes.

- Put your fingers in your ears and block out as much sound as you can.

- Set a timer for one minute. Use this time to take in your surroundings using only your eyes. Try to get a sense for the dimensions of the space. What do you see happening?

- Now, remove your fingers from your ears (you should already notice a big difference).

- Reset the one minute timer. Close your eyes, and once more take in your surroundings – what about the space jumps out at you now? What do you hear happening?

- Consider: how was what you heard different from what you saw?

Now, I cannot pretend to speak for you and your observations. So indulge me in listing some of my own observations, taken from my conducting this experiment at my desk with the windows open:

With my eyes open, ears shut:

- I kept checking the timer.

- I was attentive to the shapes, textures, and details of things in the room with me – I took time to consciously direct my gaze out the window and take in the depth of my available view, running my attention steadily outward.

- I kept my head moving, trying to bring new information into my eyes.

- My breath and the circulation of my blood sounded oppressively hot and close in my head, even as I tried to pay attention to my visual surroundings.

With my eyes closed, ears open:

- The timer going off caught me by surprise.

- I could perceive things I had been unable to see – I heard: my neighbor mowing their lawn, a wind-chime on the other side of the house, the breeze rustling the leaves, a car passing on the road outside, chickens outside the window – these things all felt as immediate as the objects on the desk had felt when my eyes were open.

- The fact that the door to the room I was in was open felt much more haunting – the wooden floor in my house popped from humidity in the next room. I would describe the sensation as ache-like; a feeling that something is not enclosed, and an implicit threat of intrusion.

- I did not move my head as much, except to turn my focus to a particular sound.

Despite the unscientific, casual nature of this exercise, I hope it is nevertheless more apparent to you how crucial our ears are to our understanding of a given space. There is a difference between seeing a crowd chanting in a stadium, and hearing – feeling – the unison of their acoustic actions. Likewise, there is a difference between a 2D interface that shows you a picture of a street in winter, and the sounds of that street bouncing on your ear drums. The physical aspect of sound – that air vibrates through a space, and is affected in subtle ways by the contours of that space before entering your ears – absolutely cannot be discounted when we consider historical soundscapes.

Searching for Samples

Now we are faced with the question: how do we recreate the acoustic character of the street ambiance outside Guy’s window? We have already done the first step: identify the sounds you want to have in the final ambient track. The next step is the real rub: find the samples you need.

Audio samples can come from a variety of places. For my part, I maintain a large library (95.6 gigabytes [Footnote 9]) of sounds I have either downloaded from various websites, inherited from older Tesseract projects, or recorded myself. It is impossible to casually browse through this library and hope to stumble upon the sound I need; there is surprisingly little room for serendipitous discovery in such a vast collection.

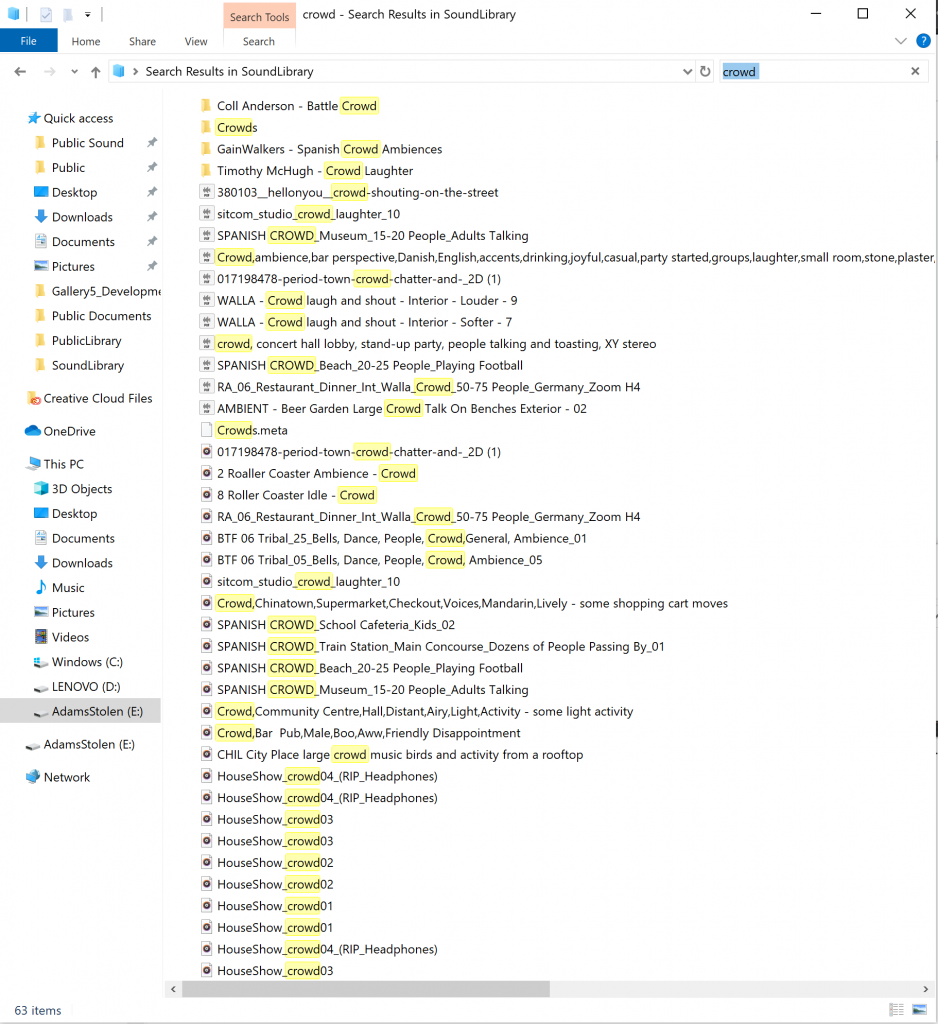

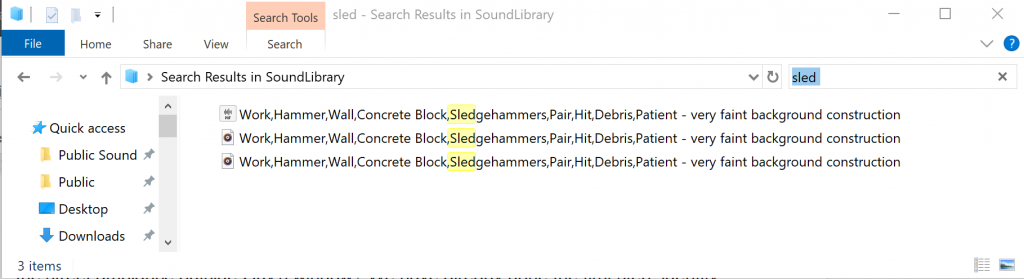

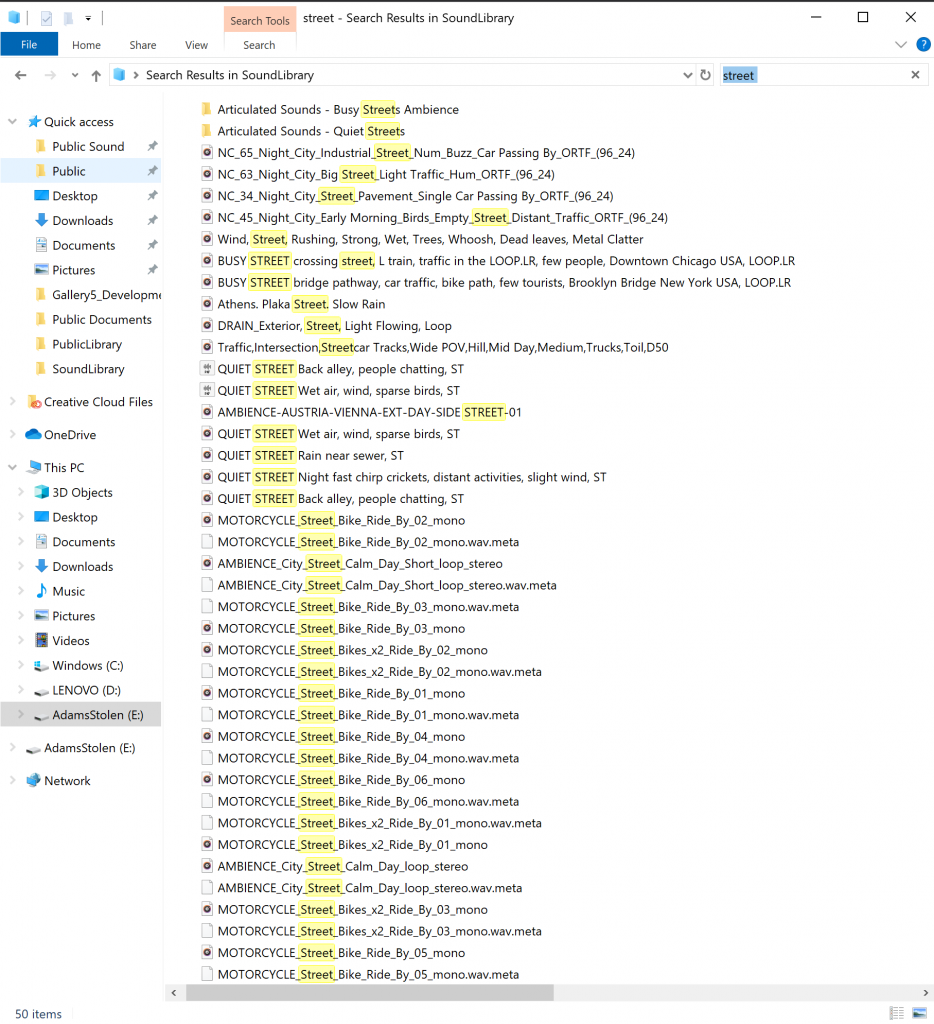

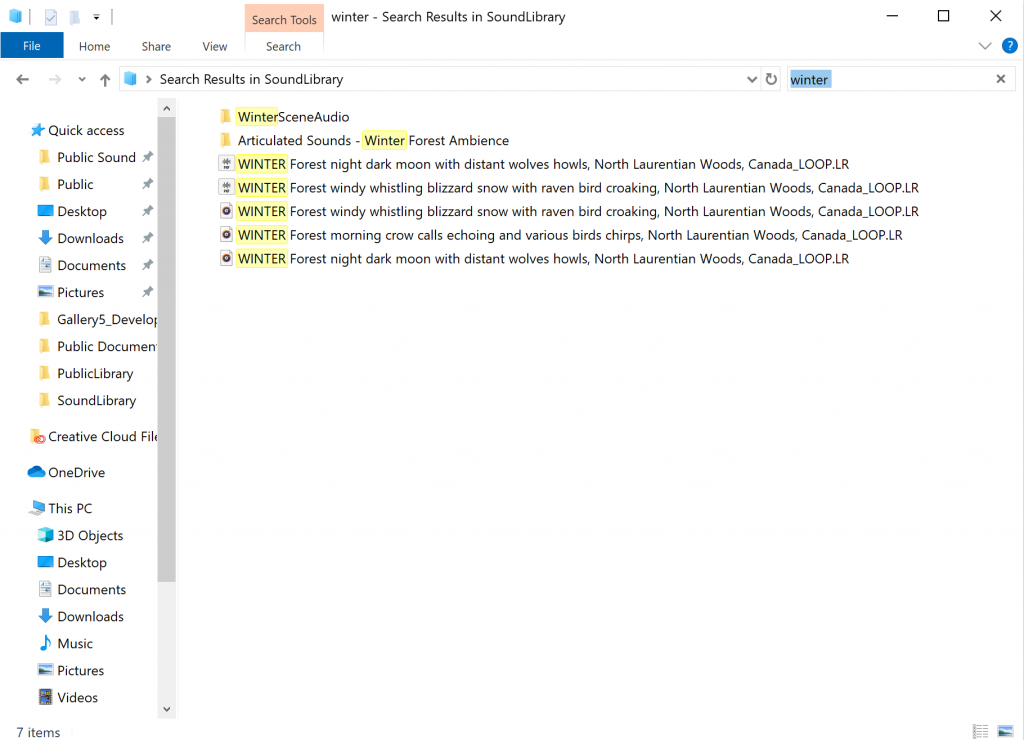

Instead I use keyword searches, hoping that the people who recorded and processed the samples have given them thoroughly descriptive file names, and have not misspelled anything. WGB’s particular acoustic demands lead to searches for sounds of: “winter,” “street,” “crowd,” “cart,” “sled,” etc.

Figure 3: A search for "cart"

Figure 4: A search for "crowd"

Figure 5: A search for "sled"

Figure 6: A search for "street"

Figure 7: A search for "winter"

Once the search function has brought up the available samples, the next step is to audition them for usefulness. This is more than making sure that the name of the file accurately describes the sounds therein – in auditioning, I’m asking a number of questions of the sample: Is there any distracting post-processing work that has been done to the sounds? Are there any extra sounds in the sample that I need to edit around? Is the sample mixed loud or quiet? Could these sounds plausibly work in the application?

This last question is no small item: most of my own effort getting samples ready for the game comes from sculpting audio recorded in the 21st century into a state that could plausibly represent the early 19th.

What this means in practice is listening for the artifacts of 21st century urban recordings – airplanes, motor traffic, cell phone ringers, anachronistic language and dialects, reverberations caused by post-/20th-Century building materials, HVAC systems with their clunks and growls, the very white noise of electricity generated by the microphones themselves. I edit around these: burying them in a mix until they are rendered incoherent, using my own post-processing software to remove offending audio frequencies, or cutting them out of the sample entirely. If the sample is too compromised by our contemporary technological noise, I move on and audition another one.

Fabricating the Soundscape

So, it is finally time to ask and answer the question: “What samples constitute my own plausible fabrication of the vibrations bouncing around Guy’s head as he studied the scene beyond his window?”

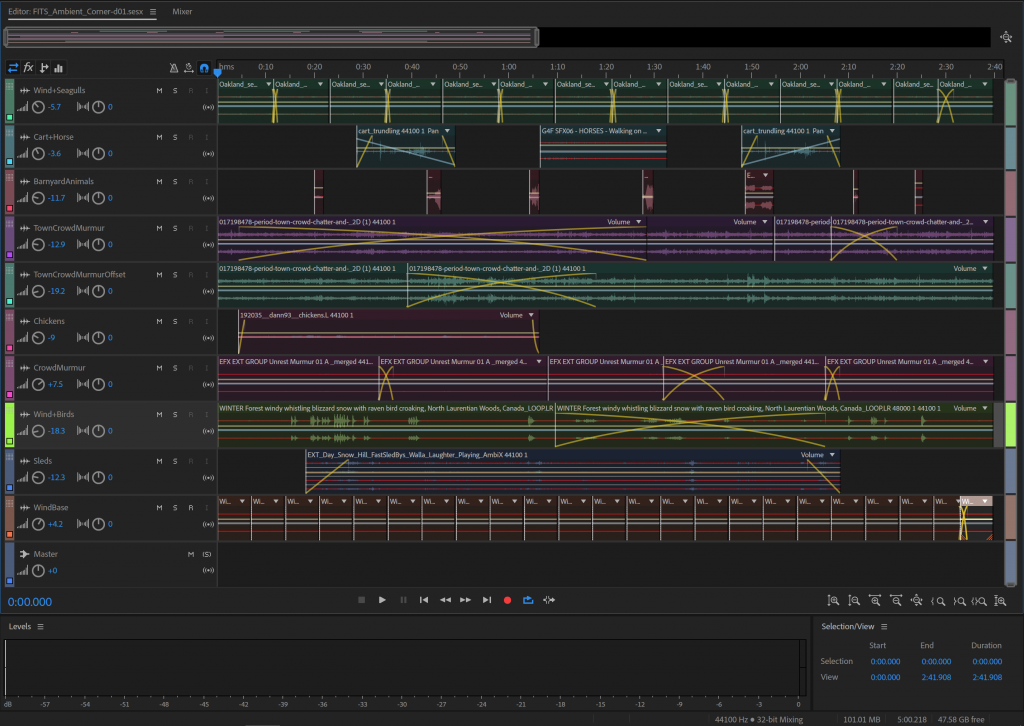

There, toward the bottom of Figure 8, is the first sound I really look for: an unobtrusive texture that functions as a kind of sonic base color. Here is the sound on its own:

If you download this sound and set this short sample to loop and close your eyes, you may find that it’s practically impossible to hear the ‘seam’ between the beginning and end of the file unless you really concentrate on the sound itself [Footnote 10]. If you let the sound play while you do other things, you’ll find that your brain accepts the continuous sound as an unbroken, immersive sonic texture: a rushing winter wind piped from your computer into your ears.

The next sound up the stack in Figure 8 – the track labelled “Sleds” – is designed to both distract from the looping base and to make the scene sound populated.

I have set this sound to fade in, play fairly quietly, and fade out. It doesn’t loop because I don’t think it’s a texture that needs unbroken presence for the entire duration of the ambient track – it is most effective in passing.

“Wind+Birds” does play continuously, however, and is made to loop with the ambient sound as a whole. It is the source of the sample I used for “WindBase,” but I have turned it down here. At full volume, the corvid cries audible in the recording would sound less like they were up and away over the smoke-puffing chimneys of the young village, and more like there was a massive crow right in the player’s face.

“CrowdMurmur” is a fun sound. It represents a specific class of voice acting that is meant to provide emotional color to background vocals, while at the same time being easy for your brain to exclude from conscious consideration. Thus, the actors in these recording sessions take pains to not actually pronounce any recognizable words [Footnote 11].

Because all the vague chattering in the sample is mere colorful nonsense, I have turned it up in the mix to fill acoustic space and mask the more distinct anthropogenic sounds present in the other samples.

“Chickens” is a sample I use here in the same way I use “Sleds.” There are chickens in the painting, so it only makes sense that the player should be able to hear some chickens.

“TownCrowdMurmur” and “TownCrowdMurmurOffset” are the same looping sound with their looping seam set at different places. This sound came from a library a friend gave me – he had done sound work for a film set in Britain during the heaviest throes of the Black Death, and this sample was meant to be a background texture for exterior shots in a high-medieval village. They recorded these sounds on-set at a pre-industrial reenactment village in Hampshire, and took pains to only roll sound when post-industrial vibrators – cars, motorbikes, airplanes, lawnmowers – passed and died down.

Here, turned down low in the mix, it lends the soundscape a sense of communal bustle while remaining out of the way, acoustically speaking. I’ve offset them so that they form a thicker texture that introduces a lot more “noise” around recognizable “signals” in the sample itself: children’s shouts and conversations just distinct enough to give the track a sense of dynamic energy without pulling the brain too deep into the nitty-gritty (and necessarily repetitious) elements of the soundscape.

“BarnyardAnimals” is similarly turned down lower in the mix to avoid the same problem “Wind+Birds” has at full volume – I don’t need an ear-splitting horse whinny, hog grunt, or cow bellow to deafen and distract the player. It is enough to have mixed-down reminders of the quasi-pastoral nature of the young Brooklyn, at a time when people raised animals within blocks of busy commercial ports and warehouses.

By now, you may have noticed that some of the shorter samples sound “grainy” or otherwise low-fidelity. Usually, this is because I have edited them out of a larger audio file that had a lot more going on across the whole frequency spectrum. However, when they are mixed down low in a busy sound, they just become one more constituent vibration.

Though the samples are spaced out over the two minutes and forty seconds of the soundscape, I put them back to back for your auditioning pleasure.

I have done the same kind of spacing out for “Cart+Horse” – I want the sound to be audible, considering there are such vehicles in the painting. But it’s not like I need to fabricate a constant stream of heavy cart traffic (we are making early Brooklyn, not antebellum Manhattan); a short sample playing every forty seconds or so will suffice to make the acoustic point.

Again, I have compressed temporally diffuse sounds into a single shorter file for your listening pleasure.

Finally, “Wind+Seagulls” provides a critical sonic texture for this street scene set a good stone’s throw away from the East River. For coastal soundscapes, seagull cries are as indispensable a sonic icon as crashing waves (though Francis Guy would likely not have been able to hear the latter from the street outside his house).

I actually recorded this sample myself a few years ago at a river-side hotel on the outskirts of Oakland, California – two-hundred years and an entire continent away from Guy’s Brooklyn. Nevertheless, for landlubbers like myself (and, I imagine, most of the game's audience), a squawking gull is a squawking gull, whatever the shining sea below them.

And with that, we have a (hopefully!) plausible fabrication of a 19th century Brooklyn soundscape. The primary reason for the 160-second runtime is to give all the constituent elements of the sound time to fade in and out, but it is also to make it unlikely that a player will actively notice that they are listening to a looping sound. Perhaps they will have an awareness somewhere in the back of their mind that the sounds bouncing against their eardrums have been carefully assembled by human hands. However, if I have done my job well, then the player won’t think twice as a street that never truly was rushes on around them.

So here, at last, for your listening pleasure: a Guy’s-ear view of the corner of Front and James Streets.

"When you do things right..."

Overall, I consider my prime directive as a sound designer for a given project to be a reversal of the Victorian maxim regarding children in social situations: I must be heard, but not seen. When I do my job well, people shouldn’t be sure I’ve done anything at all (to paraphrase the above clip).

I think this must go double for games like WGB, which have as their lofty ambition the goals of faithfully representing real (and plausible, rational fabrications of) historical people and places, and educationally engaging players within these settings. The “historical” does come first in “historical fiction,” after all.

With that said, I do still think there is still some creative wiggle room available to sound designers working on history-based games. Moreover, taking advantage of this wiggle room – really fleshing-out soundscapes, making juicy and expressive sounds to accompany rote actions as apparently petty as opening a player-character’s inventory and clicking on the items therein, knowing when to lay the sounds on thick and when to let a scene breathe – will result in better, more engaging games that are ultimately more faithful to the lived acoustic experiences of the characters they represent – not in spite of their hyper-realistic aural tendencies, but because of them.

The fact is that it is entirely possible to not listen: our brains are remarkably talented at making subconscious editorial decisions about which particular vibrations are the wheat of signal, and which are the chaff of noise. I think there is a case to be made that many of the iniquities represented in Winter Scene in Brooklyn and in WGB – the ills of institutionalized racism, systemic sexism, xenophobia, economic exploitation, and discriminatory thoughts and actions of all stripes – arise when human beings (by choice or by blissful ignorance) do not listen to the pained cries of their neighbors, do not listen to the Transatlantic howls of agony, do not listen to the westward-receding sobs of sorrow.

They may not listen. We may not listen. But every action vibrates the air column, and every vibration plays our eardrums; it is only the truly deaf who are completely unable to hear them, and it is only the truly heartless who hear them and are unmoved.

Footnotes

Footnote 1:

This passage is intended less to denigrate the predominance of the visual in Eurogenic cultures (like that of the United States) than to contrast the relative concreteness and accessibility of the visual with the general ephemerality of the audible. Overall, this passage is informed by: John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1972); Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969).

Footnote 2:

In reference to Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville’s phonautograph, the first known invention designed to produce a physical-visual representation of (in his words, “photographing”) sound. See: “Origins of Sound Recording: The Inventors,” National Parks Service online, last updated July 17, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/historyculture/origins-of-sound-recording-edouard-leon-scott-de-martinville.htm, accessed April 29, 2020.

Footnote 3:

In reference to Thomas Edison’s phonograph, developed with help from Charles Batchelor and John Kruesi. See: Ibid, https://www.nps.gov/edis/learn/historyculture/origins-of-sound-recording-thomas-edison.htm, accessed April 29, 2020.

Footnote 4:

In reference to the advent of magnetic tape recording in the 1940s-50s, which represented a major leap forward in terms of capturing the acoustic spectrum and reducing the impact of incidental noise from the technology itself on the final recording. See: Andre Millard, “Tape Recording and Music Making” in Music and Technology in the Twentieth Century, ed. Hans-Joachim Braun (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), pp. 158-67.

Footnote 5:

For a brief overview of oppressive noise in various cultural contexts – as well as a dramatic tale of contemporary noise aggravation – see: Bianca Bosker, “Why Everything is Getting Louder,” The Atlantic online, November 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/11/the-end-of-silence/598366/, accessed April 29, 2020.

Footnote 6:

Specifically: S. Wood, The Cries of New-York (New York: The Juvenile book-store, 1808), now available online from the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, https://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/4134805, accessed April 29, 2020.

Footnote 7:

Henry Stiles, A History of the City of Brooklyn, v. 1-3 (Brooklyn: Published by subscription, 1869).

Footnote 8:

To a point, of course – it’s not like we feel (or really want to feel) bullets tearing into our flesh when we play shooter games, nor do we feel the G-forces acting on our bodies in racing games, and we should be thankful that we cannot smell the virtual effluent that characterizes so many sewer levels in so many games.

Footnote 9:

The reason for this gargantuan filesize is twofold. For one, many of the samples in the library are WAV files – a so-called “lossless” file type, meaning that it encodes audio data with a minimum of digital compression, striking a balance between file size and preserving the original character of the recorded sound (favoring the latter, somewhat) – and many of these WAV files are recordings of the ambient sounds of various locations, which can be anywhere from one to ten minutes long, depending on the whims of the person recording the sample. The other reason is the sheer volume of files in the library: counting all the samples and their metadata, there are (at the time of writing) 27,455 files distributed through 1,369 folders – and I sometimes still can't find the sound I need!

Footnote 10:

This largely depends on what kind of loop function you are using. A professional one like that of Adobe Audition, Audacity, or the Unity Engine will allow you to hear a seamless swath of white noise. Something like Windows Media Player or Groove Music may generate a short ‘pop’ as it moves its tracker from the end to the beginning of the clip.

Footnote 11:

For more on this particular world of background voice acting, I recommend listening to: “The Voices Hiding in Your Favorite Movies,” Every Little Thing (Gimlet Media: December 4, 2017), podcast, https://gimletmedia.com/shows/every-little-thing/2oh92r.