When we here at Tesseract set out to transform an online Roman Civilization course into a video game, we didn’t do so simply because games are fun; we did so because the medium lends itself to a unique style of pedagogy that engages students in ways unlike standard lecture-based methods…its own kind of language, if you will. Games leverage interactivity, a trait unique to the medium, to communicate with players and enable players to express themselves. There are many ways that interactivity manifests itself within a video game, but the most direct method is through gameplay, which most fundamentally arises from what designers refer to as “game mechanics.” However games are made up of more than just mechanics. Another important aspect that provides context and drives meaning is the game’s narrative. When developing a game for commercial release, these two elements, gameplay and story, can be enough to compel immersion and teach players, through the language of games, a plethora of skills and thought processes. However when developing a game for consumption within a university for course credit, accuracy and specific learning goals must be taken into account. In Saeculum’s case the prevalent element of academic concern is that of historical and cultural authenticity.

Authenticity. That’s a tricky word, especially for a writer. Any kind of representation, whether it is based on digital data points, artist interpretation, or even the way light is received and interpreted within the human eye, is subject to question when it comes to the word “authenticity.” In an earlier post, studio director and producer Dr. David Fredrick wrote: “the game and its virtual environment do not have to be literally accurate in order to teach ‘accurately.’” This is a loaded statement which I will help unpack in later posts, but we can at least begin to examine what this means by taking a surface-look at how story, gameplay, and history were balanced to leverage the experience we wanted to bring students who played Saeculum.

Before jumping into Saeculum, let’s take a step back and talk about why we at Tesseract have devoted ourselves to a narrative-focused video game approach within such an educational context.

Narratives are one of the most fundamental constructs we as humans understand, loving both to create and consume them no matter what our “official” professions may be. Stories affect many people in many different ways, shaping the way we make sense of the world around us, helping us connect with others, influencing and inspiring us, and giving us respite from the cares of everyday life. Stories help us internalize and understand concepts that, while comprehensible without, would otherwise be much more difficult.

I can tell you the girl sitting in the corner is sad, and you can believe me; you can even observe her hunched posture, that she shields her face from others, and her eyes’ red outlines belie the recent presence of tears. However if I were to tell you a story about why she was sad and how it happened, you would be much more readily capable of feeling empathy toward her.

Another, very different, example is Einstein’s theory of general relativity. I can tell you that spacetime warps in the presence of gravity, but this is much more easily understood when presented in a story like the way it is in the film Interstellar.

In the movie, this concept is made clear through human experience and emotion; not only is the story enjoyable, but it helps elucidate what can be a difficult scientific concept to internalize from our limited perspectives.

With this in mind, let’s turn our attention to Saeculum. To overcome the ways in which story, gameplay, and history fight with one another, we must first understand where these conflicts lie. From a purely narrative perspective it’s easy to assume that we all want our stories to be interesting, filled with drama, humor, and well-developed characters. Stories, whether they be fiction, non-fiction, or somewhere in between, depend on the craft of the writer to simulate what we, as audience members, perceive to be an acceptable reflection of reality or the reality we choose to accept when entering the story’s magic circle. No story is a completely accurate reflection of reality, and to be honest I don’t think any of us want them to be! For example, writers simulate dialogue, not transcribe actual conversations. Numerous elements of story-crafting must bend to the writer’s craft in order to create an engaging experience; these elements range from what events the author chooses to show us, the perspective from which we perceive events, and the timescale at which events unfold before us.

This fundamental principle of storytelling puts it directly at odds with history, which, in contrast, demands the exact opposite: cold, hard facts (or at least what we have been told from our sources or gleaned from artifacts) that value precedence on what really happened, enthralling narratives be damned.

Gameplay, likewise, seems at first glance to be at odds with storytelling. The simplest way to explain how story and gameplay butt heads is that “story” places control in the hands of the author while “gameplay” places control in the hands of the player; when crafting a story these two elements naturally fight against one another.

Games’ greatest strength, interactivity, is the core dispute around which authorial control of the experience hinges. This, however, is what makes designing for and playing an experience like Saeculum so rewarding!

Saeculum’s story takes place over five distinct time periods in Roman history, ranging from 220 BCE to 360 CE. Each of these arcs feature a contained story documenting the ups and downs of a Roman family, the Fulvii. From the perspective of the course’s learning goals, such a wide breadth of time was necessary; Rome changed drastically over time, most famously from Republic to Empire, and these realities had to be reflected from a historical point of view. The time periods we selected, however, were strategically chosen to maximize where we could best teach about the different facets of Roman civilization, while at the same time construct an interesting narrative to give players a touchstone from which to enter a different culture.

In the second arc, which is set between 140-120 BCE, players assume the role of an actual historical character, Marcus Fulvius Flaccus, mentioned in the ancient Greek author Plutarch’s Lives of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus. In the third arc, players assume the role of Terentia, a fictional character, yet one who is believably connected to important members of the Fulvii. This gives players an opportunity to interact with important characters of the time, most notably Rome’s first emperor Augustus.

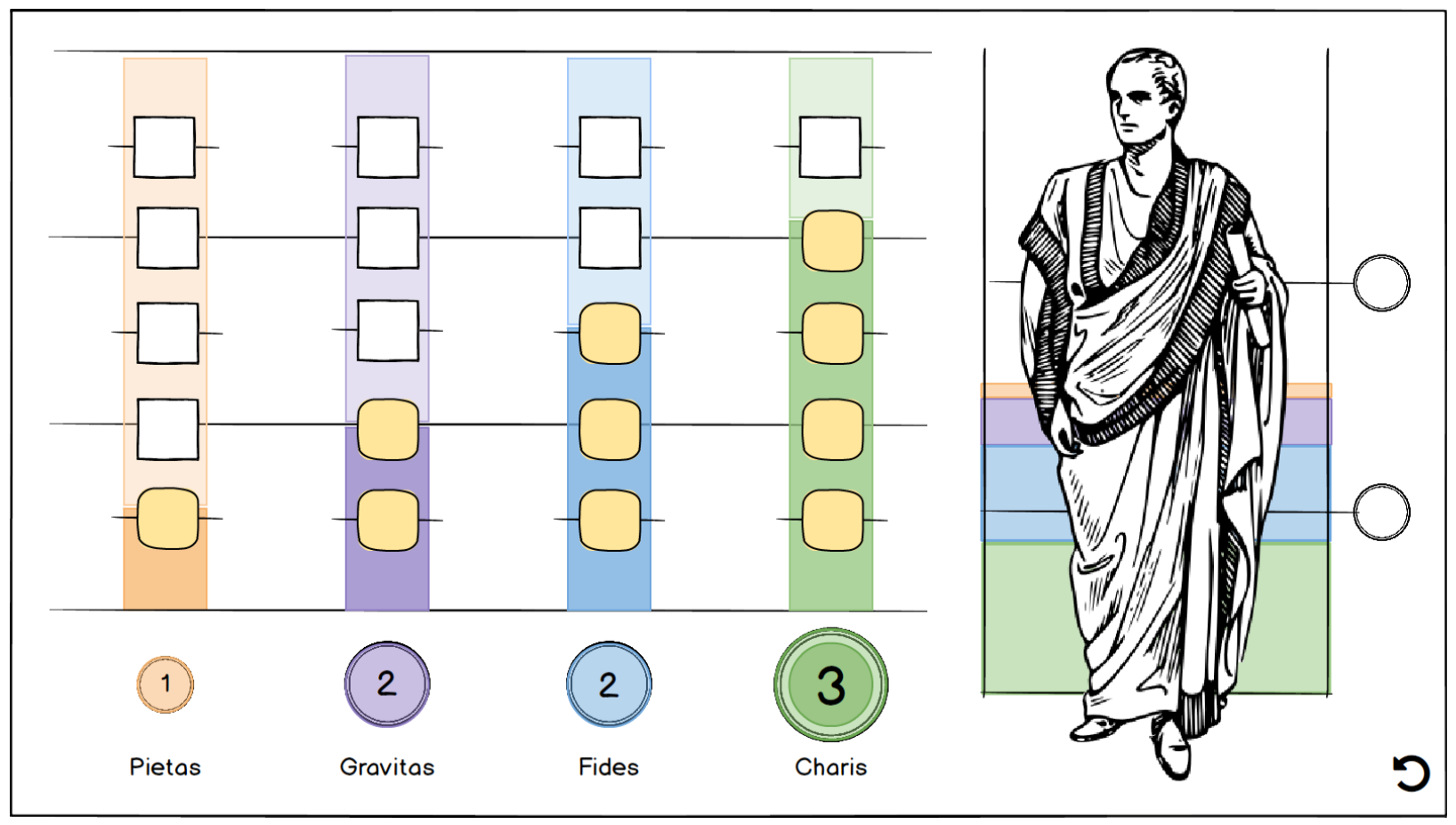

Beyond the narrative, Saeculum’s game systems add an additional layer through which students can interact with and understand Roman culture. Two of the game’s most prominent systems are “Virtues” and “Catena.”

One of the defining characteristics of Roman society was a complex relationship between patrons and clients; patrons were expected to look after the well-being of their clients and clients were expected to support their patrons, both in business and in politics. Within Roman society, there were many “virtues” that defined a person’s personality, encompassing all aspects of Roman culture.

In Saeculum, we enable players to engage with Roman culture as imagined through historical fiction. The choices players make define what kind of a person they are within Roman society. Player characters are defined by four primary virtues: Pietas (devotion to one’s family, the Roman state, and the gods), Gravitas (a sense of seriousness and self-importance), Fides (reliability and trustworthiness, especially between patron and client), and Charis (weight of personality or Charisma). Earning experience points in each category allows players to grow in strength in a manner reflective of each respective virtue. This is indicated by earning “Talents” that make players more powerful in combat, more adept in debates, and make those who follow them, their clients, more effective.

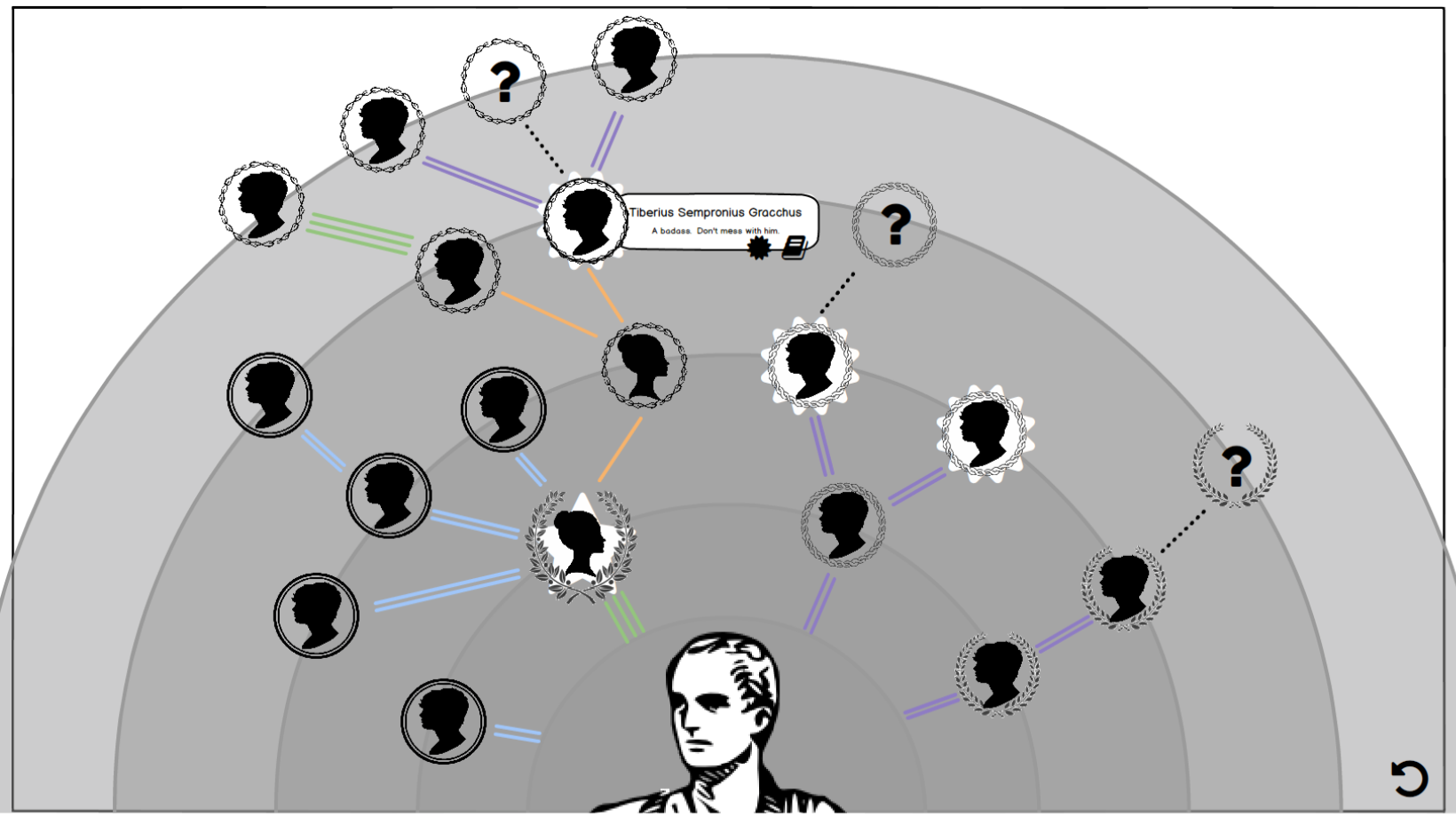

The player must also observe and make decisions based on how they are connected to other characters in the story (many of them historical!) through a system called Catena (Latin meaning “chain” or “link”). Through Catena, players see how their characters are connected with others, and how these interlocking relationships defined Roman civilization.

This was just a peak into the exciting development of Saeculum. Next week I will be taking a more detailed look into one specific area of the game’s design, Level Design, and how we work to create fun game levels that still remain true to the historical realities of Rome’s urban landscape.